The Four Agreements of Incident Response Matty Stratton DevOps Advocate & Thought Validator, PagerDuty @mattstratton

Slide 1

Slide 2

@mattstratton

Slide 3

🔥📟 @mattstratton Who has been on one of those phone calls where you are trying to troubleshoot an issue when something’s going wrong, and you’re trying to problem-solve with fellow human beings? Who really enjoyed that experience and wants to do it all the time? Incidents can be really tough, but there are ways to make them less stressful. That’s what we are talking about today.

Slide 4

@mattstratton What exactly is a incident?

Slide 5

@mattstratton Before we can respond to an incident though, we need to define what an incident actually is. It sounds silly, but if you’re not sure whether something’s an incident, you don’t know whether to respond to it. It’s critical that you have a specific definition of an incident for your organization. There is no right or wrong version of one. But you need to have one. And it needs to be clear, memorable, and widely shared.

Slide 6

An unplanned disruption or degradation of service that is actively affecting customers’ ability to use the product. @mattstratton Here is PagerDuty’s definition of an incident. Yours might be different, and that’s OK. I just wanted to give you an idea of the kind of definition that can get you started. You want your definition to be simple, no more than a sentence, and easily understood by anyone. But you may notice that this is quite a broad definition. A typo technically fits this description. As does a full outage. Obviously these are very different scenarios. So we do have something else too.

Slide 7

@mattstratton Discuss major incident, which requires coordination. More granularity can matter as well, SEV-1, SEV-2, etc.

Slide 8

50,000 responders receiving a total of 760 million notifications ▸ 60 million notifications during dinner hours ▸ 82 million notifications during evening hours ▸ 250 million notifications during sleeping hours ▸ 122 million notifications on weekends ▸ A total of 750,000 nights with sleep-interrupting notifications ▸ A total of 330,000 weekend days with interrupt notifications @mattstratton PagerDuty commissioned a study across over 10,000 companies over 100 different segments.

Slide 9

The most meaningful metrics on attrition ▸ Number of days where a responder’s work and life are interrupted ▸ Number of days when a responder is woken overnight ▸ Number of weekend days interrupted by notifications. @mattstratton

Slide 10

@mattstratton

Slide 11

The Four Agreements • Be Impeccable with Your Word • Don’t Take Anything Personally • Don’t Make Assumptions • Always Do Your Best @mattstratton Don Miguel Ruiz’s book, The Four Agreements, presents a code of personal conduct based on ancient Toltec wisdom to help remove self-limiting structures and beliefs. Each of the Four Agreements can help us understand a more mature, effective, and humane approach to incident response in our organizations. In this talk, I will address how the Agreements can be expressed as a modality for Incident Response. Using the Agreements, it is easier to understand modern approaches to resolving incidents as effectively as possible, and even help reduce burnout as well!

Slide 12

Be Impeccable With Your Word @mattstratton

Slide 13

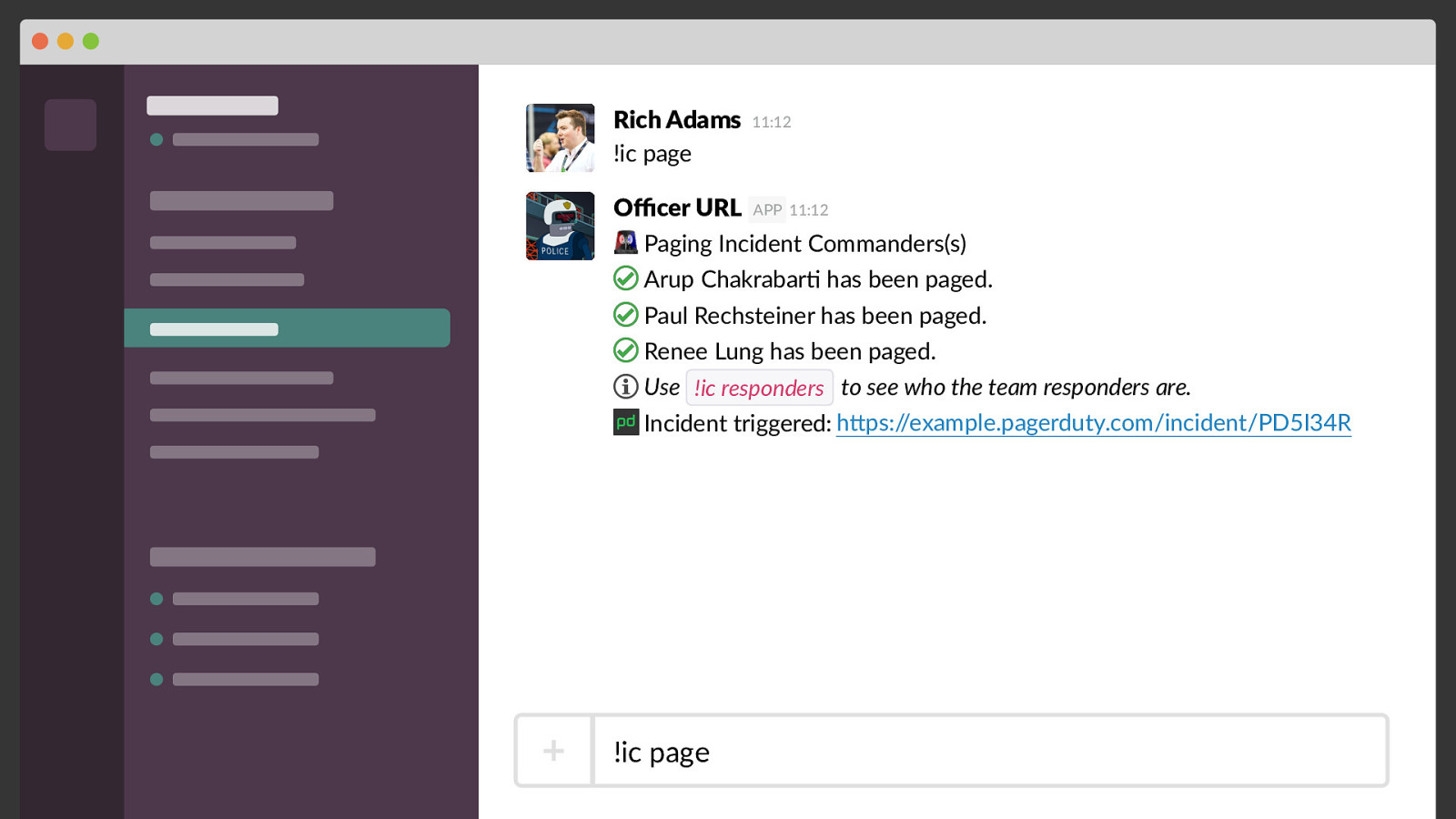

Rich Adams !ic page 11:12 Officer URL APP 11:12 Paging Incident Commanders(s) Arup Chakrabar: has been paged. Paul Rechsteiner has been paged. Renee Lung has been paged. Use !ic responders to see who the team responders are. Incident triggered: h@ps://example.pagerduty.com/incident/PD5I34R !ic page So how do we let humans trigger the process? We do it with a chat command, but don’t feel like that’s the only right way. I just wanted to demonstrate how we do it to give you an idea. You can do it however your want. Air horn, flashing light in the office, hire a mariachi band, etc. The point is, you want some way to trigger your response, that’s fast, easy, and available to everyone.

Slide 14

@mattstratton Anyone can do it. The cleaning staff walking past an information display that shows things are going pear-shaped. We don’t want to have to sit and figure out if things require response, because by the time we do so, they most definitely will.

Slide 15

@mattstratton Don’t litigate severity during a call. What does this mean?

Slide 16

@mattstratton Don’t discuss incident severity during the call. If we can’t decide between two, we always assume it’s the higher severity and move on. Don’t litigate severities during an incident. It’s a waste of time.

Slide 17

@mattstratton Notify your stakeholders

Slide 18

@mattstratton It’s critical to keep involving stakeholders in the process, giving them a way to stay up to date. At PagerDuty we have a separate Slack room just for incident updates. It’s less noisy than our main response room, and gives succinct updates for folks who want it. This allows execs to stay in the loop, and also ask questions without affecting the main response. In our process, the Internal Liaison is responsible for monitoring and updating that channel.

Slide 19

Be Impeccable With Your Word • Anyone can trigger incident response • Don’t litigate severity • Notify stakeholders @mattstratton

Slide 20

Don’t Take Anything Personally @mattstratton

Slide 21

PEACETIME WARTIME @mattstratton Once an incident is triggered, we need to switch our mode of thinking. We need a mentality shift. We want a distinction between “normal operations” and “there’s an incident in progress”. We need to switch decision making from peacetime to wartime. From day-today operations, to defending the business. Something that would be considered completely unacceptable during normal operations, such as deploying code without running any tests, might be perfectly acceptable during a major incident when you need to restore service quickly. The way you operate, your role hierarchy, and the level of risk you’re willing to take will all change as we make this shift. “Fire isn’t an emergency to the fire department. You expect a rapid response from a group of professionals, skilled in the art of solving whatever issues you are having.” [Quote from Blackrock 3] - http://www.blackrock3.com/blog/incident-management-meets-it-operations

Slide 22

NORMAL Some people don’t like the peacetime/wartime analogy, so you can call it what you want. Normal/Emergency. EMERGENCY @mattstratton

Slide 23

OK Or OK/NOT OK. What you call it isn’t as important as being able to make the mental shift. NOT OK @mattstratton

Slide 24

@mattstratton This means that during an incident, a lot of things change. And one of those things has to do with how we communicate. It doesn’t mean we can be jerks to each other. But we are focusing on our goal, which is to handle the situation in a way that limits damage and reduces recovery time and costs.

Slide 25

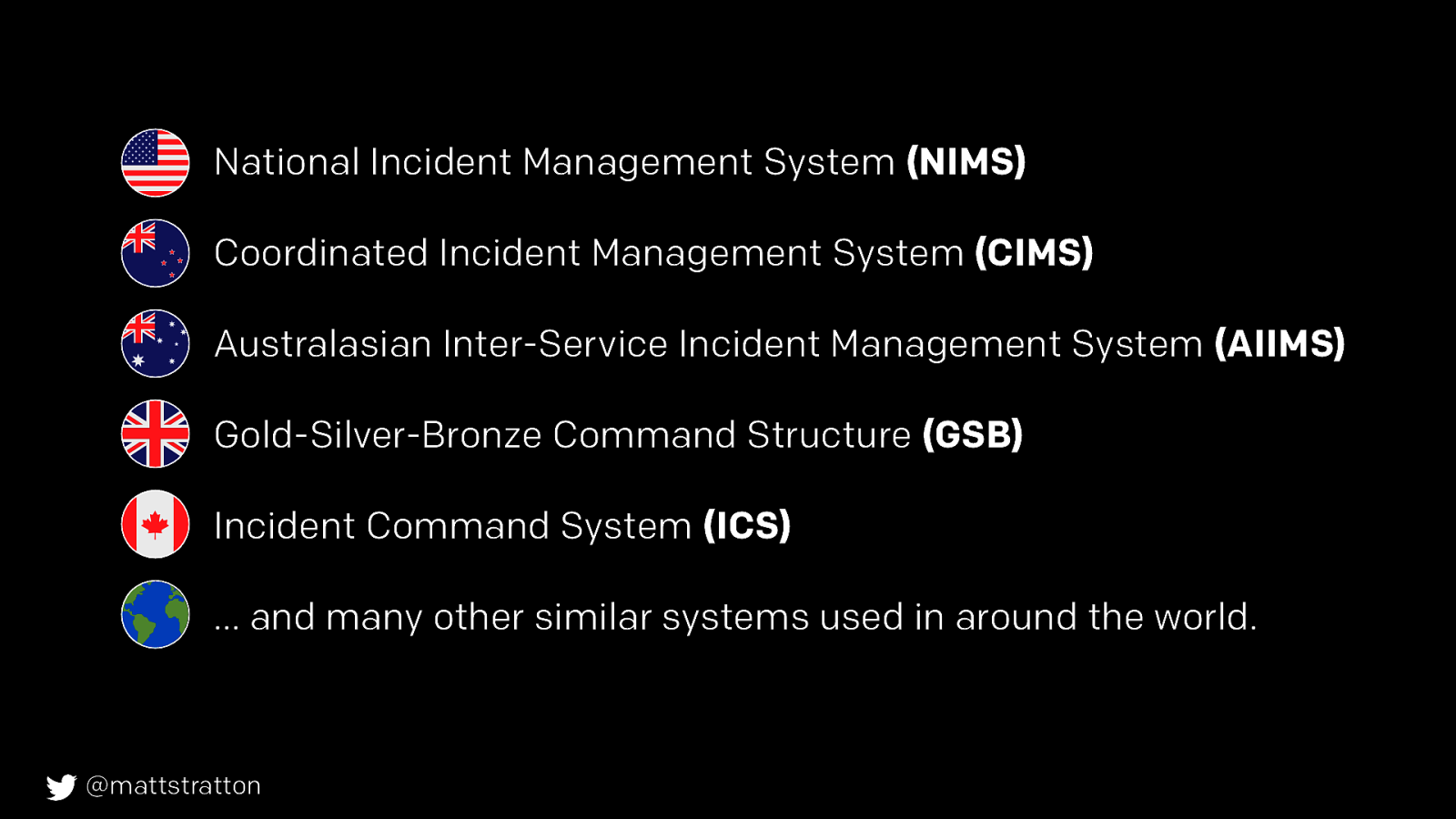

National Incident Management System (NIMS) Coordinated Incident Management System (CIMS) Australasian Inter-Service Incident Management System (AIIMS) Gold-Silver-Bronze Command Structure (GSB) Incident Command System (ICS) … and many other similar systems used in around the world. @mattstratton It’s worth noting that even though our process is based on the US systems, NIMS and ICS, there are many similar systems in use all over the world. While many are also based on ICS, some were developed separately, yet offer many of the same features. I particularly like the UK system, simply because it has a role called the “Gold Commander”, which just sounds like a Bond villain. When developing our process at PagerDuty, we looked at a few of the other systems in use around the world, and chose the bits we liked the most to add to our own system. There’s also a book available from the US FEMA website, called “Comparative Emergency Management: Understanding Disaster Policies, Organizations, and Initiatives from Around the World” if you’re interested in learning more about the systems in use. It compares the systems used by about 30 different countries.

Slide 26

@mattstratton At the top of our process is someone called an Incident Commander. Let me tell you a little bit about the IC.

Slide 27

@mattstratton The Incident Commander has the role to delegate and coordinate. They make decisions. They’re the single source of truth during an incident, and are the ones in charge. They make all decisions, and no action should be performed unless the IC has said so. White helmet story. Blah blah blah IC, Deputy, other roles, SME

Slide 28

@mattstratton This is a tricky one. The IC is the highest authority on the call, even outranking the CEO or other management. Make sure you get buy-in from management BEFORE or this will not go well for you. Don’t take this personally.

Slide 29

@mattstratton Of course, sometimes you have to help people understand this new way of working. And it can be tricky. Especially with executives.

Slide 30

@mattstratton

Slide 31

@mattstratton When the executive is coming in and trying to take over, it’s quite simple. Let them take over. Say “Are you taking command of the call?” If they say “yes”, great. Most of the time, they won’t say anything and you can move along.

Slide 32

@mattstratton This can make you feel pretty crappy. The implication is that people aren’t working as hard as they could.

Slide 33

@mattstratton While this can sound really demotivating when it happens, stay professional. Don’t take it personally. Say “we are in the middle of resolving an incident. Please keep your comments to the end” or direct them to the appropriate communication channel/liason. Remember that your execs aren’t trying to make things worse - they are trying to help. Don’t take it personally.

Slide 34

Don’t Take Anything Personally • Switch in mindset • Incident Commander is the highest authority • Incident Commander is not a resolver • Executive Swoop @mattstratton

Slide 35

Don’t Make Assumptions @mattstratton

Slide 36

This background is blue. @r_adams Let’s look at a quick example to show what I mean. I propose that this background is blue. Does everyone agree? (Point to about 5 different people in the room one by one and ask if they agree). See how long it’s taking us to reach consensus? Distributed consensus is hard, you’ll be there forever trying to agree on the proposed actions. Let’s try it a different way though. I propose that this background is blue. Are there any strong objections? … Hearing none, background is blue, let’s proceed.

Slide 37

@mattstratton One of the most essential terms in your toolkit is “Is there any STRONG objection?” We are optimizing for the 99%. This also prevents hindsight effect (“I knew that wouldn’t work”) as well as emphasizing we are not looking for the most perfect solution.

Slide 38

@mattstratton Avoid jargon

Slide 39

@mattstratton When we put in a lot of jargon (i.e., “Let’s get the IC on the RC and get some BLT’s for all the SME’s”) we add a lot of cognitive overload. This also can make newcomers feel excluded. Clear rather than concise.

Slide 40

@mattstratton So now it’s time to assign tasks to help resolve an incident. We are going to tell our SME’s the things they need to do. How do we do this?

Slide 41

@mattstratton A couple critical items here. Make sure tasks are assigned to specific people. And they need to be time-boxed. And definitely make sure they are acknowledged. Avoid bystander effect. “Can someone…” is deadly.

Slide 42

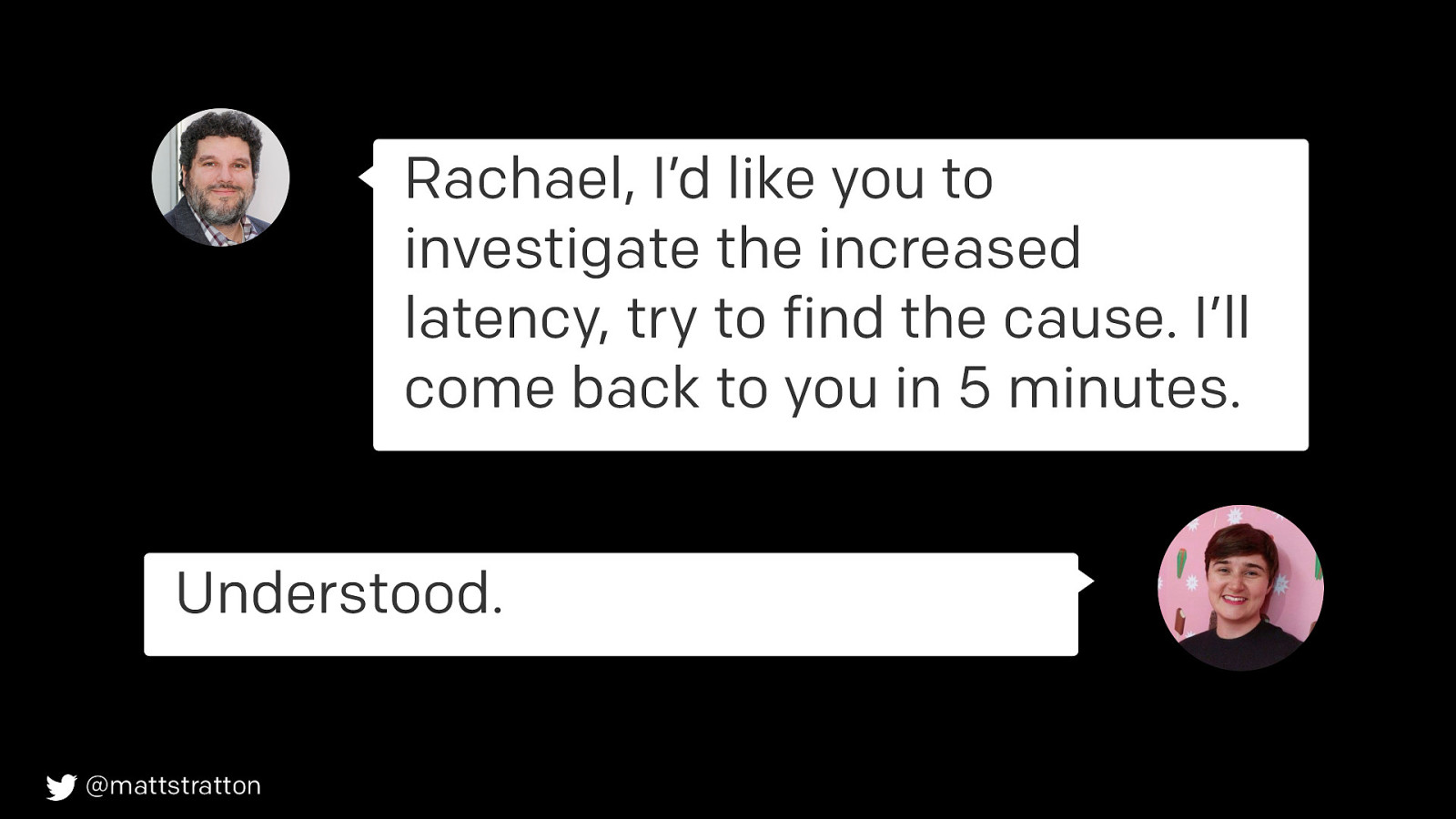

Rachael, I’d like you to investigate the increased latency, try to find the cause. I’ll come back to you in 5 minutes. Understood. @mattstratton What’s different here? It’s a little more verbose than “Can someone”, but several important things happened in this exchange.

Slide 43

Don’t Make Assumptions • Consensus is hard • Clear is better than concise • Assign tasks to a specific person • Time-box all tasks @mattstratton

Slide 44

Always Do Your Best @mattstratton

Slide 45

@mattstratton It’s better to make the wrong decision than no decision at all.

Slide 46

@mattstratton Wow, is that a controversial statement. But here’s the thing…making the wrong decision provides you with more information. Making no decision? We get stuck in analysis paralysis.

Slide 47

@mattstratton Rally fast, disband faster

Slide 48

@mattstratton Can get so many people on a call - it’s really expensive in terms of both money and effort. Super stressful for everyone. Way better to get people in when you need them but let them go.

Slide 49

@mattstratton Do responders get tired? Do IC’s get tired? Of course we do.

Slide 50

@mattstratton Handovers are encouraged. It’s quite easy to do - bring in the new person to shadow for a bit, and you just tell everyone what’s happening!

Slide 51

@mattstratton

Slide 52

@mattstratton Post-mortems not only should be blameless, but only useful if you actually learn from them. Don’t do them just to fill out a form. Write-only post-mortems are useless.

Slide 53

@mattstratton Review your process regularly

Slide 54

@mattstratton Continuous improvement! Quarterly, annually, whatever it is…make sure you’re asking the right questions. For example, at a certain point at pagerduty, everyone was paged on a critical incident. That works at a small size. But it doesn’t scale as the org gets bigger, etc.

Slide 55

DON’T PANIC @r_adams Don’t panic. It elevates stress, and causes others to panic. It’ll end up hurting your incident response a lot more.

Slide 56

@mattstratton It’s OK to panic on the inside. We’re only human after all. It’s a natural reaction to panic in these sorts of situations a little bit. Everything about getting paged is designed to get adrenaline flowing. Loud pager sounds and so on. Just don’t ever outwardly show panic, because it will cause others to do the same. Act calm, and others will follow suit. We trained with some ex-firefighters to learn about incident response, and something they mentioned stuck with me. They would often come to a house fire, and the owner would be historical “Oh my god, you have to help…”, etc. It’s understandable of course, but they were actually hindering their progress. The firefighters would have to tell them, “This might be your first fire, it’s not ours”. Fire isn’t an emergency to the fire department, it’s routine. Those with experience will stay calm, and that can make the difference between a chaotic incident, and one that resolves smoothly. So don’t panic.

Slide 57

Always Do Your Best • Better to make the wrong decision than no decision • Rally fast, disband faster • Handovers are encouraged • Useful post-mortems • Review your process • Don’t Panic @mattstratton

Slide 58

@mattstratton

Slide 59

speaking.mattstratton.com @mattstratton

Slide 60

@MATTSTRATTON LINKEDIN.COM/IN/MATTSTRATTON MATTSTRATTON.COM ARRESTEDDEVOPS.COM SHARE YOUR ON-CALL STORIES WITH ME LATER @mattstratton