Matty Stratton, DevOps Evangelist, PagerDuty @mattstratton Incidents & Accidents If appropriate, “Can someone keep track of time for me?”

Slide 1

Slide 2

@mattstratton I used to talk about what I do and who I am, but nobody really cares.

Gratuitous slide of kids to get you on my side

Slide 3

Who here has been on one of those phone calls where you are trying to troubleshoot an issue when something’s going wrong, and you’re trying to problem-solve with fellow human beings?

Who here really enjoyed that experience and wants to do it all the time?

Incident calls can be really tough, but there are ways to make them less stressful.

A lot of organizations just make it up as they go along, but there are things we can borrow from first responders, and other best of breed disciplines to help make this better.

Slide 4

@mattstratton Disclaimer, part the first: Learn from other industries, do not take on their stresses. I’ll be showing a bunch of stuff here. Some of it comes from ATC, some comes from first responders - these are folks who deal with literal life-or-death situations.

Inherit the interesting things we can learn from them, but don’t take on their stress. There’s no reason that a sysadmin needs to have the stress level of an air tra ffi c controller.

Hopefully most of you don’t have the situation where a down system causes someone to die. For those of you who do… that’s an awesome responsibility and I have nothing but respect for you carrying that mantle.

Slide 5

@mattstratton Disclaimer, part the second: This is a topic with a surprisingly large number of details. Second disclaimer - this is a surprisingly large topic. It might seem as simple as “we all just get on a bridge and work the problem and the site is back up”…but it’s a complex system.

For example, there is the business impact, business continuity, etc, through to organizational factors (which team owns what?), getting down as precise as individual psychology, and how different individuals deal with stressful situations.

This is a short talk that only begins to touch upon the larger system.

Slide 6

@mattstratton “Peacetime” PEACETIME WARTIME We need a distinction between “normal operations” and “there’s an incident in progress”. We need to switch decision making from peacetime to wartime. From day-to- day operations, to defending the business.

“Fire isn’t an emergency to the fire department. You expect a rapid response from a group of professionals, skilled in the art of solving whatever issues you are having.”

The way you operate, your role hierarchy, and the level of risk you’re willing to take will all change as we make this switch.

Slide 7

@mattstratton “Peacetime” NORMAL EMERGENCY Some people don’t like the peacetime/wartime analogy, so you can call it what you want. Normal/Emergency.

Slide 8

@mattstratton “Peacetime” OK NOT OK Or just OK/NOT OK. The key is to make the mental shift.

So let’s talk about our process a bit more. The way we perform incident response isn’t something we invented ourselves…

Slide 9

@mattstratton Before, during, after This will be broken up in to three sections

Things you should do before you ever get into an incident call

Things you should do DURING an incident

Finally, things you should do after.

There are different things to perform and consider at each of these phases, and all three of them are equally essential.

Slide 10

@mattstratton Before

Slide 11

@mattstratton Have criteria defined for when to have and not have a call. The most important thing to do before is have criteria of what causes an incident?

This should all be driven by business-related criteria. For example, it could be that order volume is 20% lower than it should be for this time of day, etc.

System-level alerts (CPU usage, disk space, etc) are not the criteria to determine if something requires a call. They may be indicators that trigger the need to make a decision, but they are not the criteria for determining if you should have one.

Slide 12

@mattstratton Any unplanned disruption or degradation of service that is actively affecting customers’ ability to use the product. It sounds silly, but if you’re not sure whether something’s an incident, you don’t know whether to respond to it. Here is PagerDuty’s definition of an incident. Your might be different, and that’s ok. Just make sure you have a definition somewhere. Keep it simple.

A typo technically fits this description. As does a full outage. Obviously they are very different scenarios. So we do have more granularity.

Slide 13

@mattstratton Post incident criteria widely. Don’t litigate during a call. You do this beforehand because you don’t want to be litigating it during the call. The call is the time to solve the problem. It’s not the time to argue about how important the problem is. During an incident it can be di ffi cult to make complex business impact decisions. We need to have these figured out when we have the luxury of time to think them through and have the proper discussions with stakeholders.

This also helps make it clear to everyone involved in the process WHY this is important to our business for us to be doing this very stressful thing that none of us want to do right now.

Post it widely, because stakeholders and others who are not directly involved with the incident will still want to be able to discover and understand what the response is…who is involved, who is doing what, what the expectations are, etc

Slide 14

@mattstratton Monitor the business criteria, and act accordingly. You may have monitoring like nagios that is focused on cpu, memory, disk, etc, but you also want to have some type of system that looks a little higher - maybe something like datadog, or an APM solution, which will help you see “hey, your business is about to have a problem, or your users are experiencing a degradation in service”

Ideally, this business or service level monitoring should work automatically to engage and start the process of incident.

You also need to watch your watchers. For example, at Pagerduty, we want to make sure we are delivering notifications within a certain amount of time. So we have a system that is constantly checking “how long is it taking, etc”. If that system is unable to determine this, that itself is criteria to start an incident - because it means we are flying blind, and we MIGHT be having a business impact, but we cannot be sure.

Slide 15

@mattstratton People are expensive. Speaking of humans…they’re expensive.

In a large organization, a bridge with 100 people sitting there mostly idle for several hours is not unheard of. That’s REALLY expensive to the organization. If each of those people cost ~$100/hour, that’s $10K every hour! Even outside of the dollar impact, there is a cost to productivity - if you have 100+ people spending hours at 2 am, they aren’t going to be getting a lot of high value work done the next day.

So when you’re deciding who is (and isn’t) going to be a part of the incident process (humans), realize this is something that is expensive to your business - and design it accordingly.

Slide 16

@mattstratton Practice still makes perfect. Practice.

As you move from the ad-hoc to the more repeatable approach, you want to practice all the steps and parts that we will talk about as the “during” section.

Practice it while it’s not stressful.

Practice it when you have total control over the situation.

Some orgs do failure injection, or if you want to be fancy, “chaos engineering” - that’s a good time to practice incident response. Game days, whatever you want to call them. At PD, when we do “Failure Friday”, we handle it like an incident, with the same process and ceremony that we would use in the real thing.

This is a safe way to try it out, since you know what the actual problem is…it gives the ability to have a bit more focus on the process and find out what works well and what doesn’t. And repeated practice creates organizational muscle memory towards this for when it’s needed at 3 am.

Slide 17

@mattstratton “Know your role” Before something happens, know the roles. Often times this happens ad hoc…but if you have to decide it during the incident, it’s taking away energy and time from solving the problem.

Slide 18

@mattstratton Have a clear understanding of who is supposed to be involved in each role. Hmm. I hear there is a company that makes a thing to help with this.

This shows who IS involved and who ISN’T. This helps absolve stress. If I know that this week I am not directly on the hook, then I can breathe easier.

Slide 19

@mattstratton https://www.fema.gov/national-incident-management-system • “National Incident Management System” (NIMS) • Incident Command System (ICS) . • Standardized system for emergency response. • Hierarchical role structure. • Provides a common management framework. • Originally developed for CA wildfire response. …it is heavily based on NIMS and ICS. Originally developed by the US government for wildfire response, it’s now used by everyone from the local fire department, to FEMA, in order to have a standardized response that everyone is familiar with.

The National Incident Management System (NIMS), a program of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), is a comprehensive approach to incident management that can apply to emergencies of all types and sizes. ICS. It’s sometimes called the Incident Management System (IMS). The terms are interchangeable.

“In 1970, series of devastating wildfires swept across CA, destroying more than 700 homes and 775 sq miles in 13 days, with 13 fatalities. 1,000s of firefighters responded, but found it di ffi cult to work together. The knew how to fight fires, but lacked a common management framework.”

Slide 20

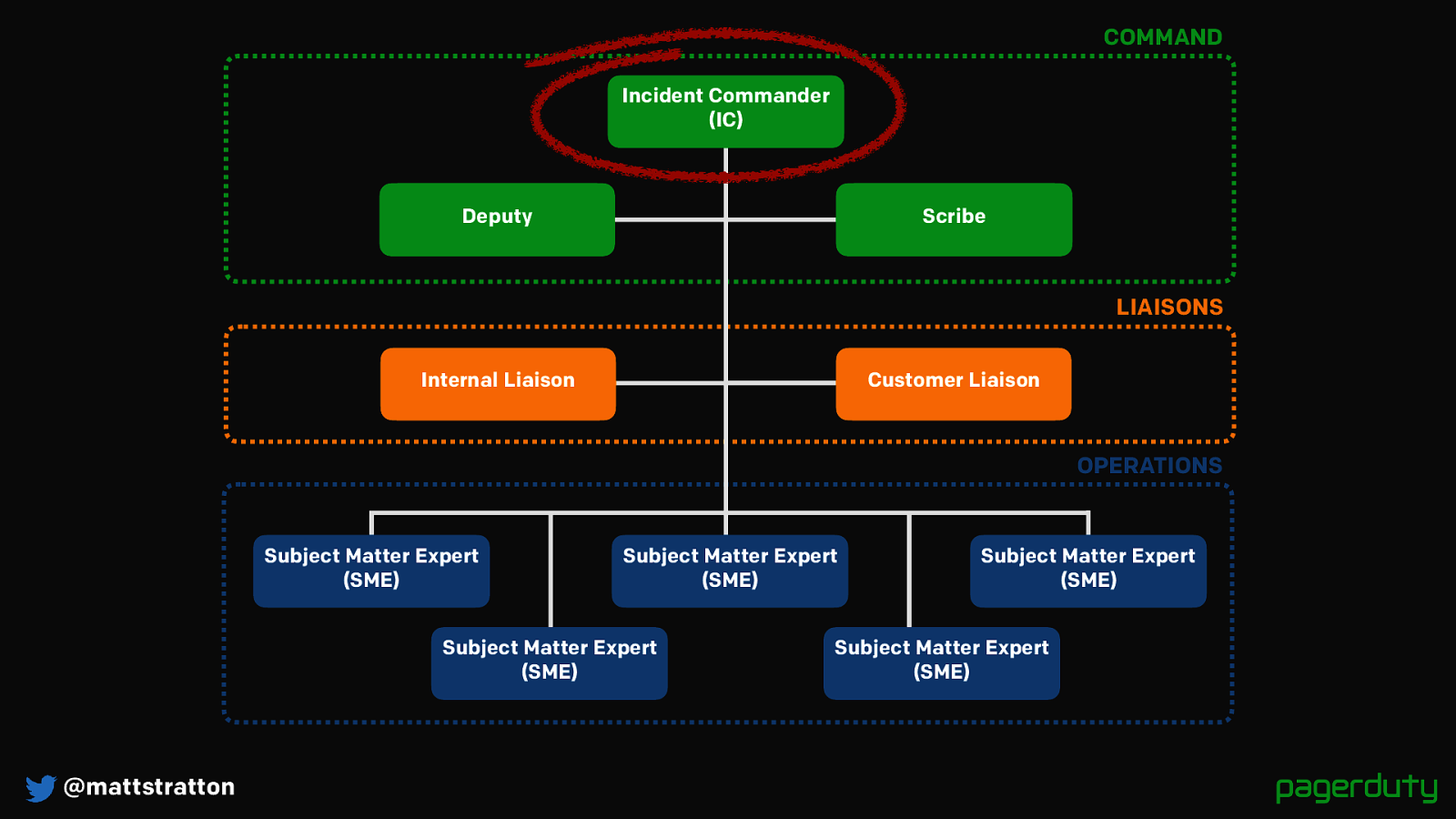

@mattstratton OPERATIONS LIAISONS COMMAND Deputy Scribe Customer Liaison Subject Matter Expert (SME) Subject Matter Expert (SME) Subject Matter Expert (SME) Subject Matter Expert (SME) Subject Matter Expert (SME) Incident Commander (IC) Internal Liaison While we don’t use exactly the same roles as ICS, we picked out the ones that matter for us in order to get our role structure.

Command: IC, Deputy, Scribe

Liaisons: Customer, Internal

Operations: SME’s

Today, I’m going to focus on one role in particular, that of the Incident Commander.

Slide 21

@mattstratton During One of the first things that happens the Incident Commander introduces themselves.

“Hi, this is Matt, I’m the incident commander. Who’s on the call?”

Stating this makes it clear. Don’t abbreviate to IC, new people might not know the lingo yet. “Commander” subconsciously instills in people that you’re in charge.

Slide 22

@mattstratton I’m Matty. I’m the Incident Commander. Every call starts like this. Introduce yourself, and make it clear you’re the incident commander.

Slide 23

@mattstratton Single source of reference. They’re the single source of truth during an incident, and are the ones in charge. The big cheese. The head honcho. They make all decisions, and no action should be performed unless the IC given the go ahead.

Slide 24

@mattstratton Becomes the highest authority. (Yes, even higher than the CEO) No matter their day-to-day role, and IC is always becomes the highest ranking person on the call. If the CEO joins, the IC still out-ranks them in an incident response situation. This is critical for successful incident response, and it does require buy-in from your executives.

Slide 25

@mattstratton Not a resolver. Coordinates and delegates. KEY TAKEAWAY Importantly, they don’t resolve the incident, they coordinate and delegate all tasks. An IC shouldn’t be looking at logs or graphs, they shouldn’t be logging into servers. This can be hard sometimes if an engineer becomes an IC, as they may naturally want to jump in to try and help, but that urge must be resisted if they’re acting as an IC.

With firefighters, the IC wears a white helmet. They have a saying, “If you see someone wearing a white helmet holding a wrench. Take the wrench off them and hit them over the head with it.”

Slide 26

@mattstratton DON’T DO THIS Let’s get the IC on the RC, then get a BLT for all the SME’s. Too many acronyms and internal lingo will upset newcomers and adds cognitive overhead. You want to favor explicit and clear communication over all else.

Slide 27

@mattstratton Clear is better than concise. KEY TAKEAWAY Clear instructions are more important than concise instructions. Favor explicit instructions over acronyms. Don’t give a long essay, but make sure the instructions are unambiguous.

But then you can get stuck in with solving the incident…

Slide 28

@mattstratton The IC manages the flow of conversation. This goes both ways. Stakeholders or SME’s are going to say “I just heard from a customer that we are having an issue, what’s going on?” The IC says “okay, I have a report that says this is going on, I’m going to get a resource from the app team to see if we’ve done any pushes lately” the IC goes through and engages the resource if they aren’t already there, and the IC tells them “here’s the problem. I’m going to give you five minutes - please come back to me with what’s going on. I’ll check with you in five minutes if I haven’t heard from you”

The IC is not the one solving the problem, but the IC is setting up the context for everybody else to work together, without everyone having to worry about who is doing what, and how to get the information they need.

Slide 29

@mattstratton What’s wrong? The first step is to collect information from team members for their services/area of ownership status. Gather the symptoms of the incident. We call this “sizing up”.

Slide 30

@mattstratton What actions can we take? Collect proposed repair actions from the experts.

Slide 31

@mattstratton What are the risks involved? You’ll be making a decision on what action to take, so ask your experts questions. “What impact will that have?”, “What are the risks involved?”, etc. Remember, delegate all repair actions, the Incident Commander is NOT a resolver.

Slide 32

@mattstratton “Can someone…” At the start, I asked if someone could keep track of the time. Did anyone actually do that? Probably not. Because of the bystander effect. Everyone assumed someone else was doing it.

Never use this phrase, you’ll hit the bystander effect. No one will actually do what you want. If someone by chance does, you won’t know who it is, or if they’ve even started.

A better approach would be, (Point to someone in front row), “You, please keep track of the time and give me a little wave when we get to 30 minutes, starting now. Understood?”. See how different that was. What about in an incident situation?…

Slide 33

@mattstratton Rich, I’d like you to investigate the increased latency, try to find the cause. I’ll come back to you in 5 minutes. Understood? Understood. What’s different here? It’s a little more verbose than “Can someone”, but several important things happened in this exchange.

The task was assigned directly to a specific person. It’s ok to assign it to a role too “DBA on-call…”, etc. But it must be a single individual.

The task was given a time-limit. The SME knows exactly how long until I come back to them for an answer, so they won’t be surprised or caught off guard.

The IC confirmed that they had understood the instructions and are going to carry them out. So I don’t come back in 5 minutes and find they never started, etc.

Slide 34

@mattstratton Humor is best in context. Humor can be really helpful.

Sometimes on an incident the team can start chasing their tail, or going down ratholes, or not being very helpful to one another. As an IC, you can use humor to move the person doing something not so great out of the flow of conversation.

This is an example clip from a JFK ATC. ATC is constantly dispatching people from point a to point b so they don’t collide with one another

Slide 35

@mattstratton

DT5: Roger that

GND: Delta Tug 5, you can go right on bravo

DT5: Right on bravo, taxi.

(…): Testing, testing. 1-2-3-4.

GND: Well, you can count to 4. It’s a step in the right direction.

Find another frequency to test on now.

(…): Sorry

It’s funny, but it moves the conversation forward. You made a joke, but you also told me what I need to do.

Incident calls don’t have to be super cut and dry; you can use humor, but in the context of moving the conversation forward.

Slide 36

@mattstratton Have a clear roster of who’s been engaged. Make sure you know who is engaged.

Have a roster of who the specific people are in each role. This is the DBA who has the thing going on, etc. This DBA hasn’t been involved.

Slide 37

@mattstratton Rally fast, disband faster. You want to get all the right people on the call as soon as you need to…but you also want to get them OFF of the call as soon as possible.

It’s super stressful to be sitting on a call saying “this is an application issue…I’m a network engineer, and I’m going to just sit on this call doing nothing waiting for them to roll it back.

This is stressful for the people doing nothing, but also for the people doing the work, who know they have this silent audience who is just waiting and watching them work.

So as the IC, start kicking people off the call who aren’t needed. And do this as fast as you can. You can recruit them back in later.

Slide 38

@mattstratton Have a way to contribute information to the call. Have an agreed upon mechanism for SME’s to contribute information to the call. Any kind of way for the SME to say “hey, IC, I have some new information for you”

Slide 39

@mattstratton Have a clear mechanism for making decisions. If it’s so easy that anyone can do it, robots should do it.

Save the call for decisions that require humans.

Slide 40

@mattstratton “IC, I think we should do X” “The proposed action is X, is there any strong objection?” This is the mechanism for making the decisions.

State it definitively.

Slide 41

@mattstratton Capture everything, and call out what’s important now vs. later. Write it all down. Document as much as possible. IF you’re able to, call out what’s important now rather than later. You might call out ideas for proactive items that came up.

Slide 42

@mattstratton “One last thing…” (Assign an owner at the end of an incident) There must be an owner assigned to the review, even though everyone wants to get off the call. You have to get it assigned before ending the call.

The IC doesn’t always have to be the owner. Just make sure it gets assigned.

Slide 43

@mattstratton After

Slide 44

@mattstratton “After action reports”, “Postmortems”, “Learning Reviews” Has everyone heard of blameless postmortems. If not, google them. Or look at the resources at the end of this deck.

Capture all that information about what went right, what went wrong…and review it afterwards. It’s incredibly valuable.

The NTSB has reports on crashes - even if they aren’t fatal crashes.

Slide 45

@mattstratton The impact to people is a part of your incident review as well. Don’t forget to think about what happened with humans because of this. Hey, someone got called at 6 pm at their kid’s birthday party, because she was the only one who knew the information. Identifying this means that you can in the future help alleviate stress on the individual, but also make your organization more resilient.

Slide 46

@mattstratton Record incident calls, review them afterwards. This is painful, but also valuable. Record them if you can. Playback at 1.5 or 2x speed

This will help you find the things you didn’t catch at the time. Or didn’t address in the review.

Slide 47

@mattstratton Regularly review the incident process itself. Continous improvement! Quarterly, annually, whatever it is…make sure you’re asking the right questions.

For example, at a certain point at pagerduty, everyone was paged on a critical incident. That works at a small size. But it doesn’t scale as the org gets bigger, etc.

Slide 48

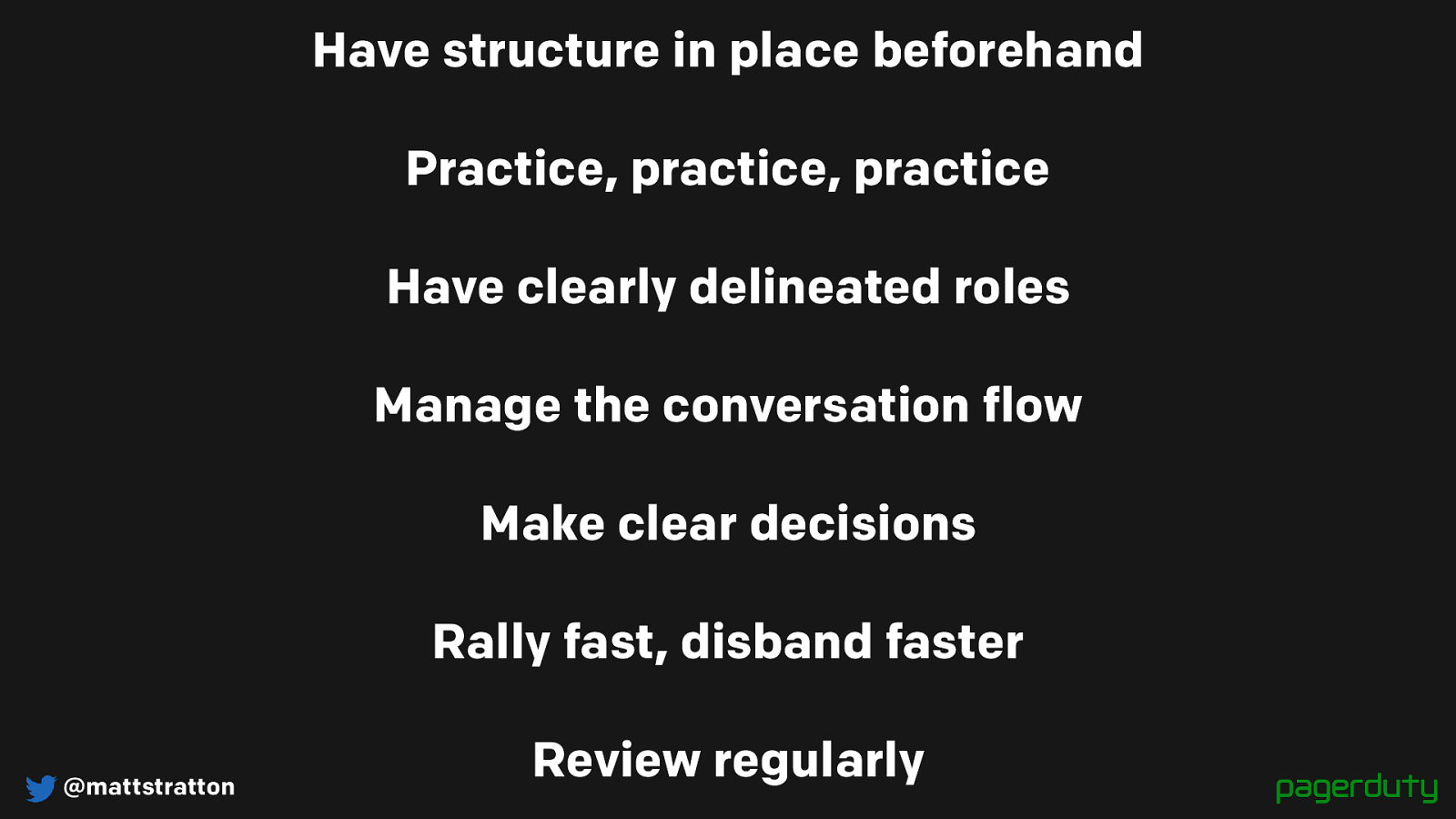

@mattstratton Have structure in place beforehand Practice, practice, practice Have clearly delineated roles Manage the conversation flow Make clear decisions Rally fast, disband faster Review regularly

Slide 49

@mattstratton Here’s some additional reading for you

Slide 50

@mattstratton Don’t panic. Stay calm. Calm people stay alive.

Slide 51

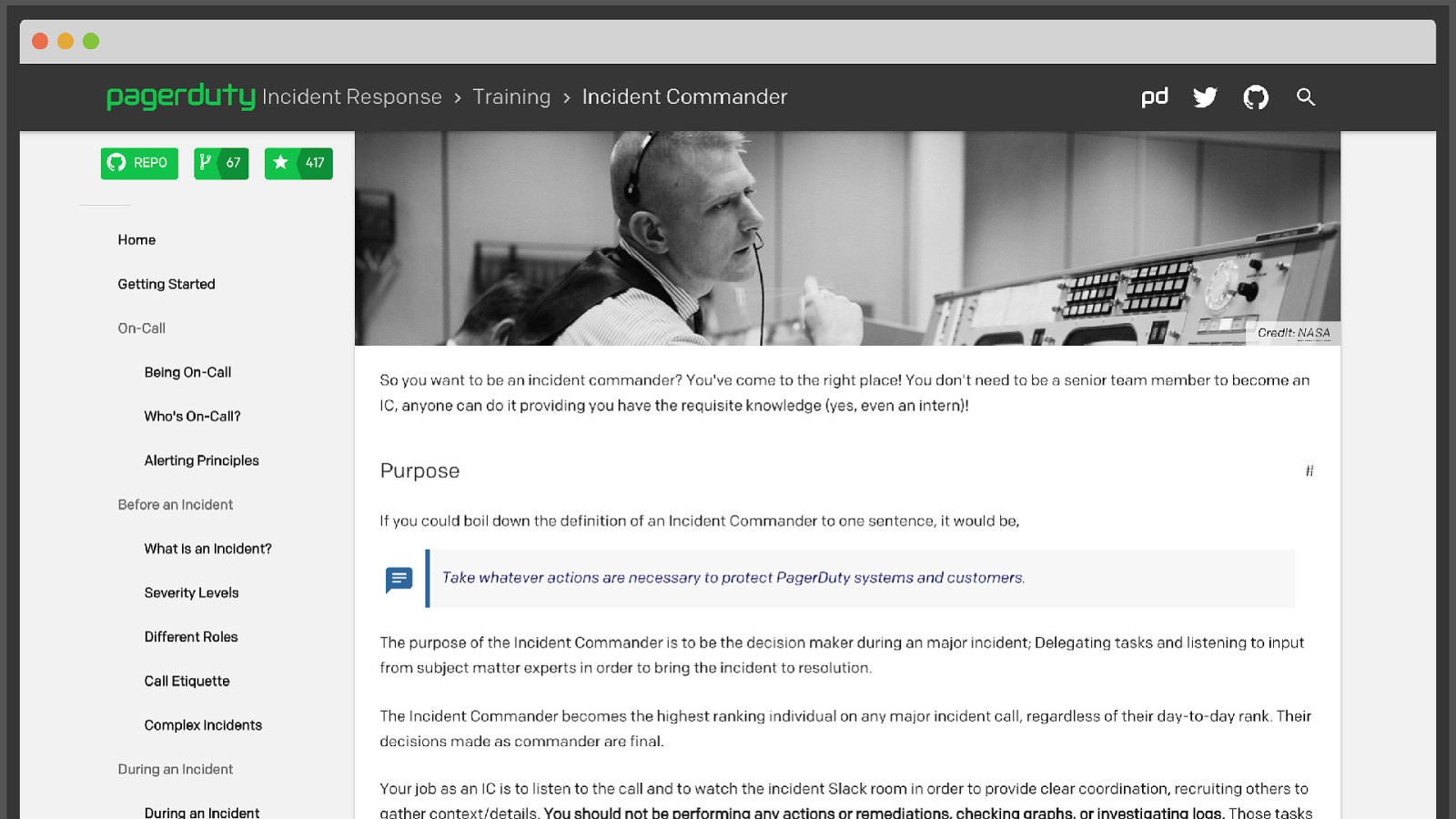

@mattstratton https://response.pagerduty.com I didn’t have time to cover a lot of our training, but just gave you a taste of the types of things that can help you right now. We have published our entire incident response process online, along with all our training material. It’s great, you should check it out. It’s also available on GitHub if you want to fork it and use it as the base for your own internal documentation.

Slide 52

@mattstratton It looks pretty too.

Slide 53

@mattstratton Resources: • Angry Air Traffic Controllers and Pilots - https://youtu.be/Zb5e4SzAkkI

• Blameless Post-Mortems (Etsy Code as Craft) - https://codeascraft.com/ 2012/05/22/blameless-postmortems/ • Incidents And Accidents: Examining Failure Without Blame (Arrested DevOps)

- https://www.arresteddevops.com/blameless/ • PagerDuty Incident Response Process - https://response.pagerduty.com/

Slide 54

@mattstratton Thank you! Questions?